Catrina McAra, (c.f.mcara@hud.ac.uk)

“Scared to death” – theory is terrifying

References taken from Cat’s lecture and Google images (text and image).

I thought by initially compressing all of the lecture onto my blog would help me with reflection and research.

This lecture was the most helpful and experimental in the aspect of research especially for my project on narratology.

Vocalisation – view point – representing architecture

– space and proximity (reference to Mozart – musical context)

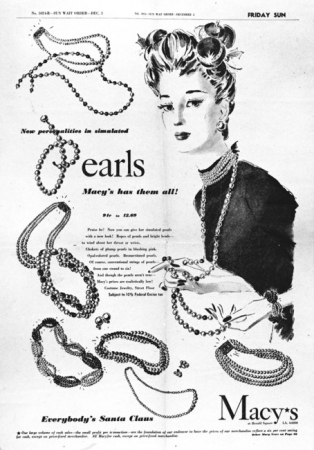

“technically gifted, depicting pearls, diminutive objects”

Tanning left this type of work behind to gain her succession as a painter.

- Greenberg would not of liked Dorothea’s work – he claims all different art has to be appropriate to their specialism,

medium is primary

differentiating the surrealist practice

Nude Art

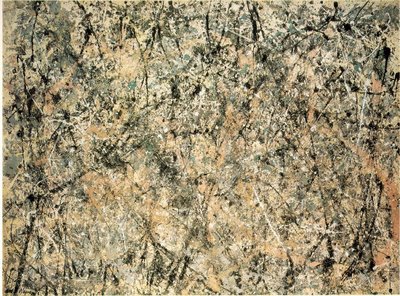

– Greenberg is interested in flatness – evolutionary practiced.

ignores the social conditions, stressing the canvas (flatness – layering the paint, not the 3 dimensional ‘taste’ through the period he persisted ignorant and simplistic)

– Linear chronology

- John Tenniel

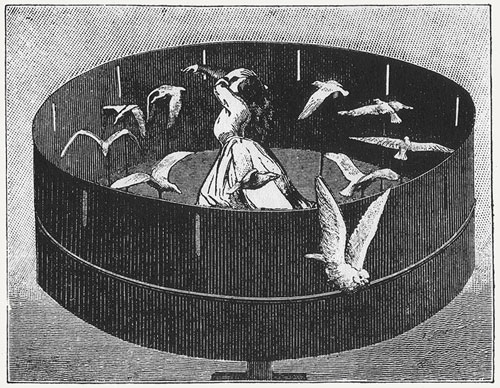

The Garden of Live Flowers, Illustration for Lewis Caroll, Through the Looking Glass and What Alice found There, Macmillan and co.London 1871

(narrative link to Dorothea Tanning – A little Night Music)

Gothic Genre

- Radcliffe – key gothic novel writer

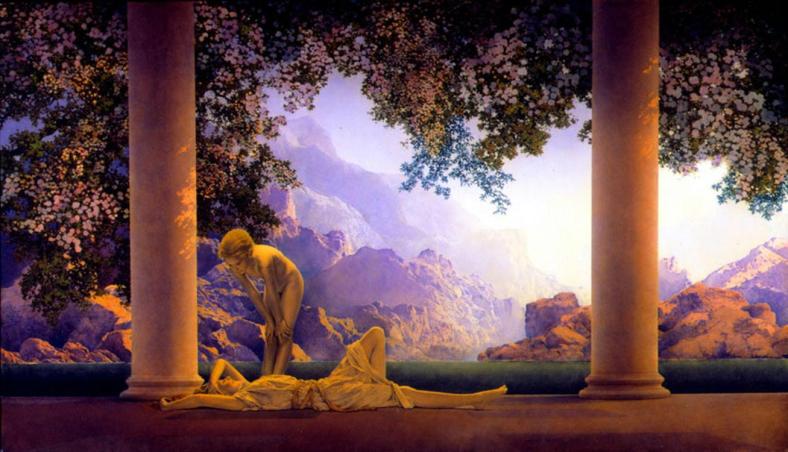

1 in 4 American households owned this print – exposure to other fairytales

– classical column’s

– present some sort of strange abstract meaning in compilation or complementary colours of blue and yellow

giving a connotation of new, birth, fresh, positive value of life

Greenberg disliked this aswell as it was appropriation to modern art.

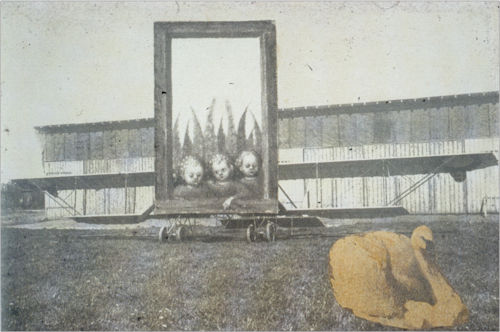

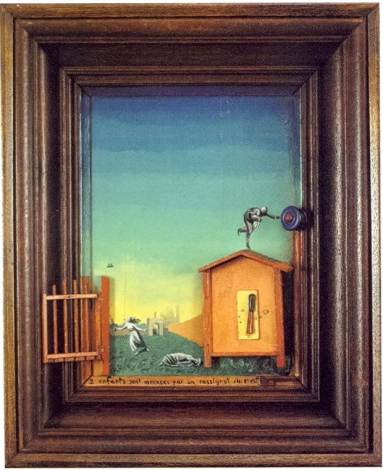

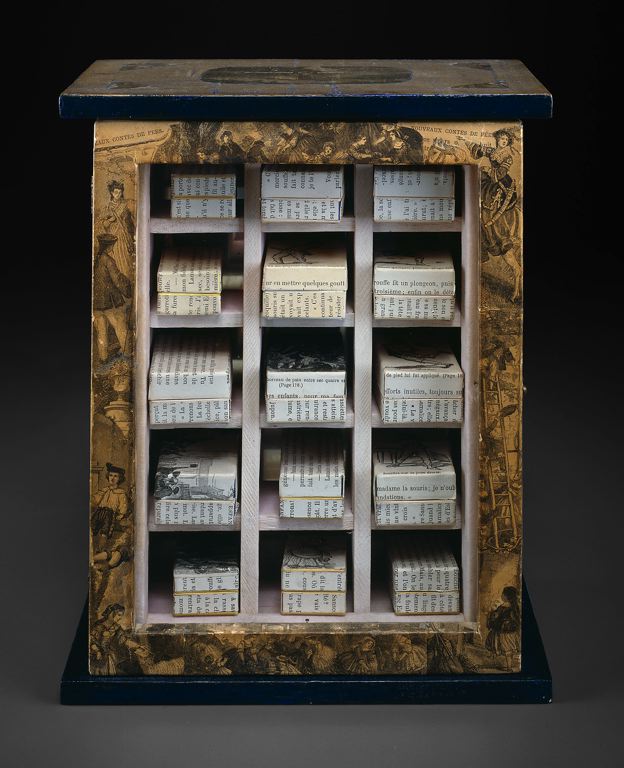

- Joseph Cornell (Dorothea’s penpal)

Nouveaux Conte de Fees (The New Fairy Tales) (The poison box), 1948

painted wood box with glass front

Lindy and Edwin Bergman, Joseph Cornell Collection 1982

Theory

Scared to death?

“A theory is a systematic set of generalized statements about a particular segment of reality”

Mieke Bal

Engagement and storytelling are important to social situations and choices

” Theories are metaphors”

Mieke Bal

Metaphors – deeper sense of meaning, used in everyday speech

two-fold; tenner, vehicle

likeness of difference

‘like’ and ‘as’ aren’t used in metaphors

reference to visual metaphors

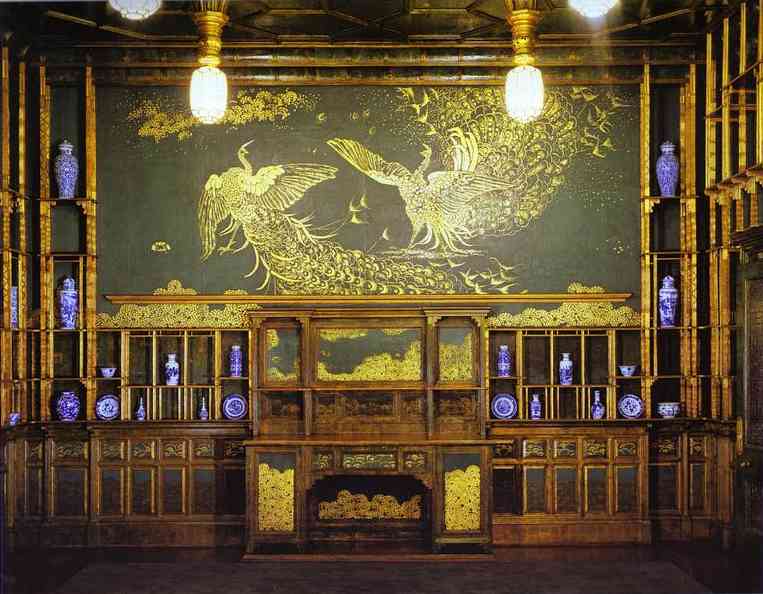

- Interior Design, Jame Abbott McNeill

The Peacock room

Whistler produced this (1876)

Surrealism – fantasy disrupt order’s (1924-1968+)

international, attitude/approach to the world

extensive transhistorical period

cultural produce, ideas are still manifested today

http://www.youtube/watch

‘Alice de Jan Svankmajer (extrait)’

Leeds Surrealist Group

– was founded in March 1994, stimulated by exchanges

wordpress – blog format

Surrealism is usually mistaken for ‘weird’ or ‘strange’, although it is not

- Max Ernst

- René Magritte

“Theory is not the opposite to practice”

using fear as a shield

– oppose fear as story telling

- Jacques- Louis David

French Revolution, democracy was installed at that point.

- J.M.W. Turner

Romanticism against neo-classical, allergy – extension of metaphor ‘destroyed’, the sky looks like its almost bleeding – industrial revolution pull away from history and myth (myth-translation of a belief)

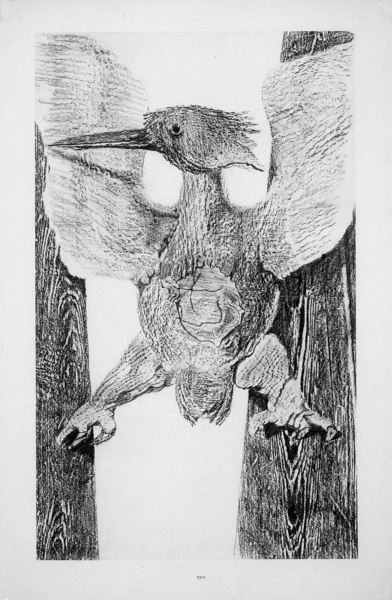

- Max Ernst

- Salvador Dalí

- Leonora Carrington

- Dorothea Tanning

- Max Ernst

Key Thinkers on the Theory of Intertextuality

See also:

“In the critic’s vocabulary, the word “precursor” is indispensable, but it should be cleansed of all connotations of polemic or rivalry. The fact is that every writer creates his own precursors. His work modifies our conception of the past, as it will modify the future.”

Jorge Luis Borges (1951)“’Influence’ is the curse of art criticism primarily because of its wrong-headed grammatical prejudice about who is the agent and who the patient; it seems to reverse the active/passive relation […] If one says that X influenced Y it does seem that one is saying that X did something to Y rather than that Y did something to X. But in the consideration of good pictures and painters the second is always the more lively reality.”

Michael Baxandall (1985)“The intertextual in which every text is held, it itself being the text-between of another text, is not to be confused with some origin of the text: to try and find the sources, the influences of a work, is to fall in with the myth of filiation; the citations which go to make up a text are anonymous, untraceable, and yet already read: they are quotations without inverted commas.”

Roland Barthes (1971)“Any text is woven entirely with citations, references, echoes, cultural languages, which cut across it through and through in a vast stereophony. The citations that go to make up a text are anonymous, untraceable, and yet already read; they are quotations without inverted commas.”

Jonathan Lethem (2007)

- Diego Velázquez

- Francis Bacon

“Bakhtin articulated any discourse is always already a patchwork of quotations. As far as discourse is concerned, there is nothing new under the sun.”

Mieke Bal (1985/1994)

- Paul McCarthy

- Robert Rauschenberg

Intertextuality in Film

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N3vpFGbudpw

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Arno_1gZ1Ro

Key Points to Take-Away and Think About

Bibliography

Bal, Mieke. Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative, second edition, London and Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997.

Bal, Mieke. ‘Scared to Death’ in A Mieke Bal Reader, 149-168. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Barthes, Roland. ‘From Work to Text’ in Image, Music, Text, translated by Stephen Heath, 155-164. London: Fontana Press, 1977.

Kristeva, Julia. ‘Word, Dialogue, Novel’ in Desire in Language: A Semiotic Approach to Literature and Art, edited and translated by Leon S. Roudiez, 64-91. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.